Cologne’s sonic legacy can mean different things depending on who you talk to. For some, it is a prestigious nexus of sound exploration, having launched Karlheinz Stockhausen on his journey after he studied at the Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln. To others, it’s a vital hub for the groundbreaking krautrock explosion, thanks to one of the most famous exponents of the sound, Can. More pioneering electronics came from the legendary producer Conny Plank, or even early 80s synthwave stars Gina X Performance. You might think immediately of Wolfgang and Reinhard Voigt’s imperious techno legacy, crystalised around the Kompakt label and their so-called ‘Cologne sound’.

These flashpoints in Cologne’s musical history are distinct, but not wholly unrelated. Stockhausen’s tutelage set Can’s members on their path, and Wolfgang Voigt’s conceptual attitude towards minimalist dance music was certainly not oblivious to this studious, experimental attitude. The differences are as important as the similarities, and at one point in the early 90s you could map out distinct factions of Cologne’s musical landscape through a cluster of shops – Groove Attack for hip-hop, house and breakbeats, Delirium for European techno (as a precursor to the eventual Kompakt shop), Formic for US techno and house, and A-Musik.

A-Musik has been going long enough to earn something like institution status, as much a stop-off for touring musicians doing an in-store show as a destination for an avid digger. You could walk into the shop today and find some relatively mainstream records, but A-Musik’s legacy and identity is rooted in experimental music. The shop also functions as a record label with a boutique quality – intermittent releases quite often from artists closely orbiting the shop and its community. They’re also a distributor, helping disseminate niche music to a network of other similarly-spirited shops across the world.

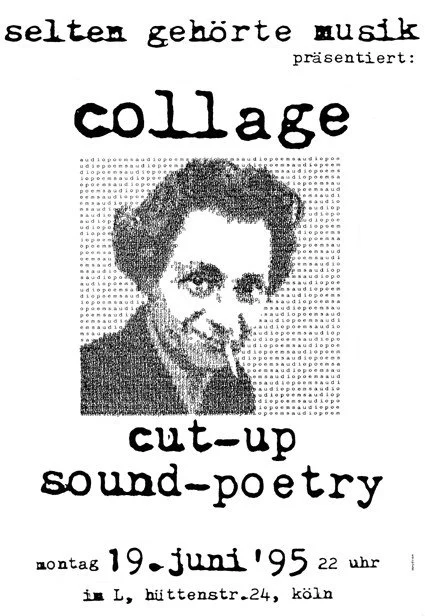

The early days

A-Musik came into being in the early 90s thanks to Frank Dommert, Georg Odijk and their close circle of friends. As with many aspects of the shop, and by extension DIY culture in general, it’s a little foggy trying to pin-point the specific beginning. The business fumbled its way out of a handful of low-key endeavours embarked upon by young music fans following their instincts in pursuit of sound.

“My background is really industrial or post-industrial music,” says Dommert. It’s a Monday afternoon in January when we connect, and the shop is closed so he can attend to the many other administrative aspects of A-Musik. “At one point I discovered electro-acoustic music and all the experimental, avant-garde rock, then I discovered quite early these records by artists like Dieter Roth for example, or Joseph Beuys and all this fine arts stuff, and then all the traditional ethnic recordings.”

As a bedrock of taste, Dommert’s musical formation is absolutely left of centre and well-informed, but he also credits one particular Cologne record shop with helping facilitate this curiosity for sound-paths less travelled. Saturn billed itself as the largest record store in the world, which they aimed to achieve by ordering every available record from any distributor they could.

“Even if they didn't sell it, they ordered it,” Dommert explains, “because they had the idea to have such a big choice. And so you could go there and buy like Zoviet France records or the UNESCO collection or Pierre Henry records, everything, and it was not expensive.”

Dommert and Odijk’s fascination with industrial music began when they were still in school, but they quickly became actively engaged with the international network of DIY labels. Dommert was linking up with Aachen-based H.N.A.S. and their Dom label before establishing his own Entenpfuhl in 1987. He released a run of cassettes his own early work and that of friends and acquaintances including the likes of C-Schulz and Marcus Schmickler before progressing to 7”s and LPs. Meanwhile Odijk had started a small mail order service for select labels, including those Dommert traded his own tapes with. Dommert released his heralded (and recently reissued) album Kiefermusik in 1990, and with other associated (short-lived) labels like Erfolg and Gefriem coming and going, by this time the cluster of friends were already busy shifting records in and out of their home.

“The beginning of A-Musik was this three-bedroom apartment,” says Dommert. “Georg, Marcus Schmickler and Jan Werner (Mouse On Mars) were living there, and there was one room which had another entrance, so Georg made this a store. The kitchen of the apartment was attached and accessible also through the store, so sometimes the door between shop and kitchen was open and somebody was cooking or eating.”

A-Musik moved from the flat in Brüsselerplatz to its first official bricks and mortar home in Cologne’s Belgian Quarter in 1995. As they grew from a node within the underground music network trade into a fully-fledged record store, they endeavoured to stock as much of the experimental music being released as possible. However, the boom of DIY music production in the 90s eventually made that pursuit untenable and they shifted their focus towards a more selective approach, combing through distributor lists, record label catalogues and reaching out to direct sources in a continuation of the work they had done trading with small labels in the early days.

Odijk was writing to labels like pivotal early electronic label Lovely Music, Ltd in New York and getting boxes of records by the likes of David Behrmann and Robert Ashley. He reached out to the publishing arm of prestigious Parisian institution GRM, INA-GRM, and acquired original stock of important electro-acoustic and musique concrete albums which would fetch monumental prices second hand these days. But while A-Musik was heading down these niche pathways towards some of the most challenging, experimental music in existence, their outlook was also maturing beyond the stubbornly closed-circuit attitude of the DIY scene.

“We became more specialised, but on the other hand I also learned through the music that things don't necessarily need to come from the DIY scene or be industrial music to be interesting,” says Dommert. “So the most famous Karlheinz Stockhausen or something can be really interesting. And at one point I realised all kinds of music can be interesting. In the store now we still have a lot of different styles and a really large secondhand section, but in the beginning all the shops in Cologne like Delirium, Groove Attack and Formic were more specialised.”

Cologne in the 90s

That the pioneering avant-garde work of Stockhausen can be considered the mainstream branch of A-Musik’s early stock says a lot about the angle they approach music from. But Cologne in the early to mid-90s had a free-spirited attitude overall, and A-Musik’s outré stance intermingled comfortably with the other threads developing in the city, woven together in a wonderfully varied, many-limbed scene.

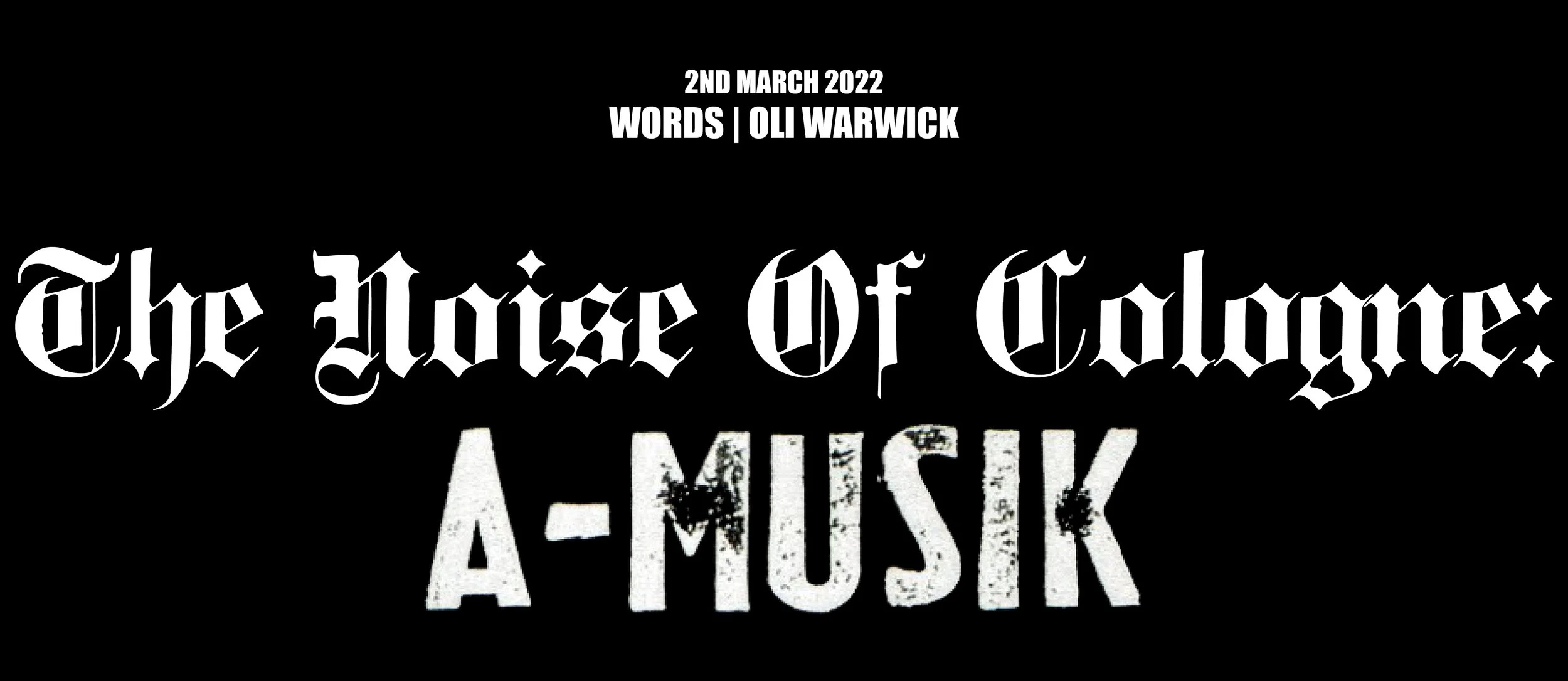

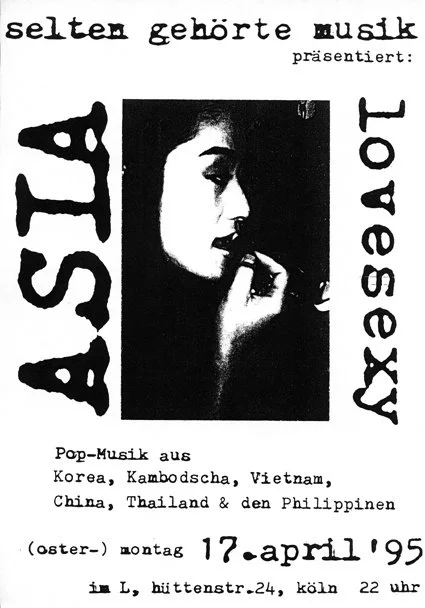

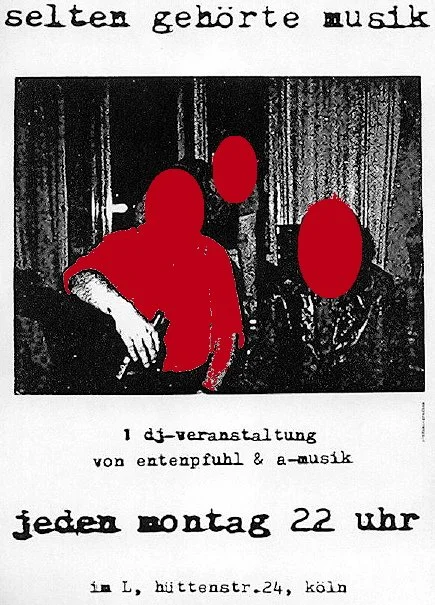

“We were active a few years before A-Musik so we had a community,” says Dommert. “We did this weekly DJ thing at a bar where we played a lot of weird music and people could connect to us and see, ‘okay, that's the guys who have this store.’ The mood in the city was very much about music. All the scenes were kind of crossed over and people were really interested in new experimental music. You could really play a Merzbow record in a bar next to a Faust or Cluster track or whatever.”

As well as reliably gliding between the distinct remits of Cologne’s record shop landscape, the townsfolk were also coming together at Thomas Thorn and Ingmar Koch’s Liquid Sky bar. This venue gathered together the techno, hip-hop and experimental communities under one free-flowing banner, typified neatly on the noise-soaked, breakbeat-powered, acid-licked slow rave killer ‘Untitled 1’ by Frank Heiss from The Liquid Sky Adventure Series - Volume One. Dommert and his fellow music misfits would DJ there on a Monday night under the banner Selten Gehörte Musik (‘seldom heard music’).

The buzz growing around the music coming from Cologne, helped no end by an expository Rob Young feature in The Wire in 1997, soon made the city a magnet for weekend trippers and long term musical migrants alike.

“Everyone was saying Cologne’s the place to be,” says Dommert, “but by the late 90s this was already gone. It was just a few years. I remember at one point, we couldn't play this weird stuff anymore in the bar. Other people came and they were more like, ‘We want to hang out. We don't listen so much to noise.’”

Even if the out-of-town allure of the city was short-lived, the latter half of the 90s saw the Cologne scene fragmenting into more defined strands as the respective forerunners matured and sought to build on the impulsive foundations of their musical endeavours. Kompakt’s techno empire is a well-known facet of Cologne music, but equally A-Musik and its satellite entities progressed in a more focused way.

The A-Musik label had begun in 1995 with the Init Ding album from Microstoria – a collaboration between Mouse On Mars’ Jan Werner and Oval’s Markus Popp. It was in 1996 that the label gathered steam though, carrying work from a largely local cast of experimental electronic artists like Marcus Schmickler (as Wabi Sabi), Jo Zimmerman (as Schlammpeitziger), and Otto Müller and Rupert Huber’s outstanding L@N project.

Over time A-Musik has released a sizable amount of music, but given the heritage of the shop and its reputation, the label retains a certain offhand quality. The artists are rarely well-known, and there’s no indication of a release schedule being adhered to. In comparison, Dommert’s own Sonig label was functioning as a thoroughly organised machine which helped build out Jan Werner’s career as Mouse On Mars and Lithops, and released a steady stream of albums and EPs in a more typical mode for electronic labels of the era.

“With a label it’s like, if you don't do it really professionally, you really need to have a relationship with the artists or the musicians,” Dommert says of the A-Musik label. “Everything has to fit. Of course, there's a lot of demo tapes we receive which we like, but we don't put them out because it's just too much work.”

One curious side-effect of the musical boom Cologne enjoyed in the 90s was that the local Office for Economic and Employment Promotion sought to capitalise on it by backing a compilation series called The Sound Of Cologne. The first volume came out in 1998, and while the two-disc offering was unsurprisingly tipped towards more accessible fare, it was certainly not an anodyne watering down of the city’s musical make up. A-Musik artists such as Schlammpeitziger, Holosud and F.X. Randomiz appeared alongside Whirlpool Productions, Mathias Schaffhäuser and Wolfgang Voigt’s Studio 1.

“They were compiled by Bernhard Lösener from Kitbuilders,” Dommert says of the Sound Of Cologne compilations, “but he was more from the techno-electronic part, and he put them together in a nice way. I think one of the later ones has also some ambient and electronic, or experimental music on but nothing extreme. I was asked to put one CD for the last volume together and at one point, I said, ‘no, that's too much,’ so we did another one which is called Noise of Cologne. I like the CDs for what they are, but they are of course missing something.”

Selling records in 2022

20 years on and A-Musik remains a destination record store now occupying a bright and airy space in central Cologne. A lot has changed in the music retail landscape, and yet there are fundamentals which hold true. Long time staff member Wolfgang Brauneis takes care of the still-busy distribution side of A-Musik. An echo of the communal spirit from the 90s period and the blurred lines between dancefloor and experimental approaches finds them often sharing distribution for new releases with Kompakt. The mail order arm of A-Musik is now the beating heart of the shop’s long-standing identity as an enclave for extreme music. The physical shop, as it has done for a long time, takes a broad view on sounds with the experimental fare balanced out by more mainstream releases for the general record shopper during this renewed wave of vinyl popularity.

”We have a lot of really young people coming in the store, which is cool,” says Dommert, “but a lot of them buy the cheap, mainstream records, like The Beatles, Pink Floyd and maybe an Abba record or Queen. Then there are some who are a bit more like younger DJs or something, but they don't know so much, and I think they have problems moving around in a store which has so many different records. They are sometimes overwhelmed because there's so much they don't know. I might add, I'm always happy when I come in a record store I don't know anything – this is the best thing that could happen to me.”

There are of course more seasoned heads who have perhaps been coming to the shop for years, but in some cases they have moved beyond what a mere record shop can offer into such hyper-specific realms of collecting, they might make one purchase a year. Still, a sense of community maintains around the shop via customers and local musicians, the wider reach of mail order and distribution, and because of A-Musik’s long-standing tradition of in-store gigs.

Community

“There's a community of collectors, listeners and friends,” says Dommert. “And there's also a community of musicians. For more than 12 years, every first Thursday of a month we had a little event or show at the store – a DJ, a musician, a lecture or somebody presenting something. So you always attract other people and some came to shop, some just to talk or to meet. Musicians would meet there for the first time and later they collaborated or got invited to small to festivals in Cologne, this sort of thing.”

Amongst the most memorable in-stores was an appearance in 2008 by Jun Kamoda, aka Japanese MC Illreme. As you can tell from the choppily edited video, it’s a rare but flawless example of someone performing a stage dive within a record shop. Dommert also looks back fondly on a talk from former Lambchop guitarist William Tyler.

One of the clearest indications of the wider musical community in Cologne orbiting the shop is the smattering of artists who have served behind the counter at different times. Perhaps the most well-known is Lena Wilikens, who worked there for a brief period and talks fondly about the experience and everything she learned about experimental music. Experimental guitar player Joseph Suchy and Durian Brothers / Institut Für Feinmotorik member Marc Matter also passed through, as well as Bambam Belay from Basspräsidium Records on a longer term basis. That said, Dommert is candid about having artists working in the shop.

“Being a musician isn't necessarily optimal for selling records, as selling is most of the time not so creative. It’s something I've experienced a lot over the years especially with interns who like records and want to become famous DJs, but are bored after 10 minutes when asked to file records alphabetically.”

The pandemic of course has had an impact on community in A-Musik as much as anywhere else, not least putting a pause on in-store gigs, but even from its relatively outlier position A-Musik serves as an essential cog within the workings of a music scene, locally and internationally. As a shop often edging towards extremes in music, the specialist interests they serve bind together people with shared passions. Even in the no-future nihilism of punk camaraderie is strong, and there remains something of the contrary punk about A-Musik.

All photos and graphics credit to Frank Dommert - additional credit to Rainer Holz - Rolf Witteler - Matt Blair | A-Musik plastic bag Design by Andrey Nikolaevich Gorokhov