“Next up we’ve got something from Seekers International, an old No Corner classic from 2014. We originally put it out on cassette, and it felt like the right time to press it up on vinyl, so I’m gonna play the vinyl now. Come down to Mickey Zoggs and get a copy if you’re in Bristol. We’ve got the stall set up now.”

It’s a mild Sunday afternoon in November and Dan Davies is on the mic, broadcasting via Bristol radio station Noods across the virtual airwaves. Davies and Alex Digard are toasting RWDFWD, their joint venture in DIY music retail, for no other reason than its very existence. The local cast of characters who pass through for the 10-hour takeover speak to the scene RWDFWD is bedded in. Between names like Kahn, Anina & Guest, Franco Franco & Kinlaw, Bokeh Versions and Lurka, there’s no single definable musical style to pin down here, just a grubby, dubby sensibility that binds these artists and friends together as they try to express themselves as best they can through various configurations of collective and collaboration. Davies and Digard have their own creative personas as Ossia and Tape Echo respectively, but RWDFWD represents the hustle side of their game.

Davies in particular has form in this regard. On the radio, or equally behind the decks at a Young Echo night in Bristol, he takes care to announce the music he plays, which more often than not comes from the constellation of labels and crews orbiting his own musical endeavours. He’s relaxed but forthright when he speaks, driven by a mission to push something he truly believes in, working every inch to make the tangle of labels, projects and releases work in the face of considerable odds.

RWDFWD came online at the end of 2012, subverting expectations about the end of days to carry music that can sometimes be considered apocalyptic. Like most underground endeavours, it wasn’t so much a conceited plan to launch an online record shop as it was a sequence of opportunities and an attempt to meet the needs of a musical community. At this time the Young Echo collective were taking shape, Digard’s Tape Echo blog and design work were in development and Davies’ Peng Sound! parties and label were finding their way through the dubwise hinterland. From modest beginnings as a Big Cartel site, it quickly became clear there was a greater demand amongst these burgeoning entities for a consolidated platform to sell the music without losing out to distributors.

It’s no secret at this point in time Davies and Digard, or rather Ossia and Tape Echo, are behind RWDFWD, but initially they wanted to maintain some separation from established labels, creative identities and other projects they were getting off the ground such as Hotline Recordings.

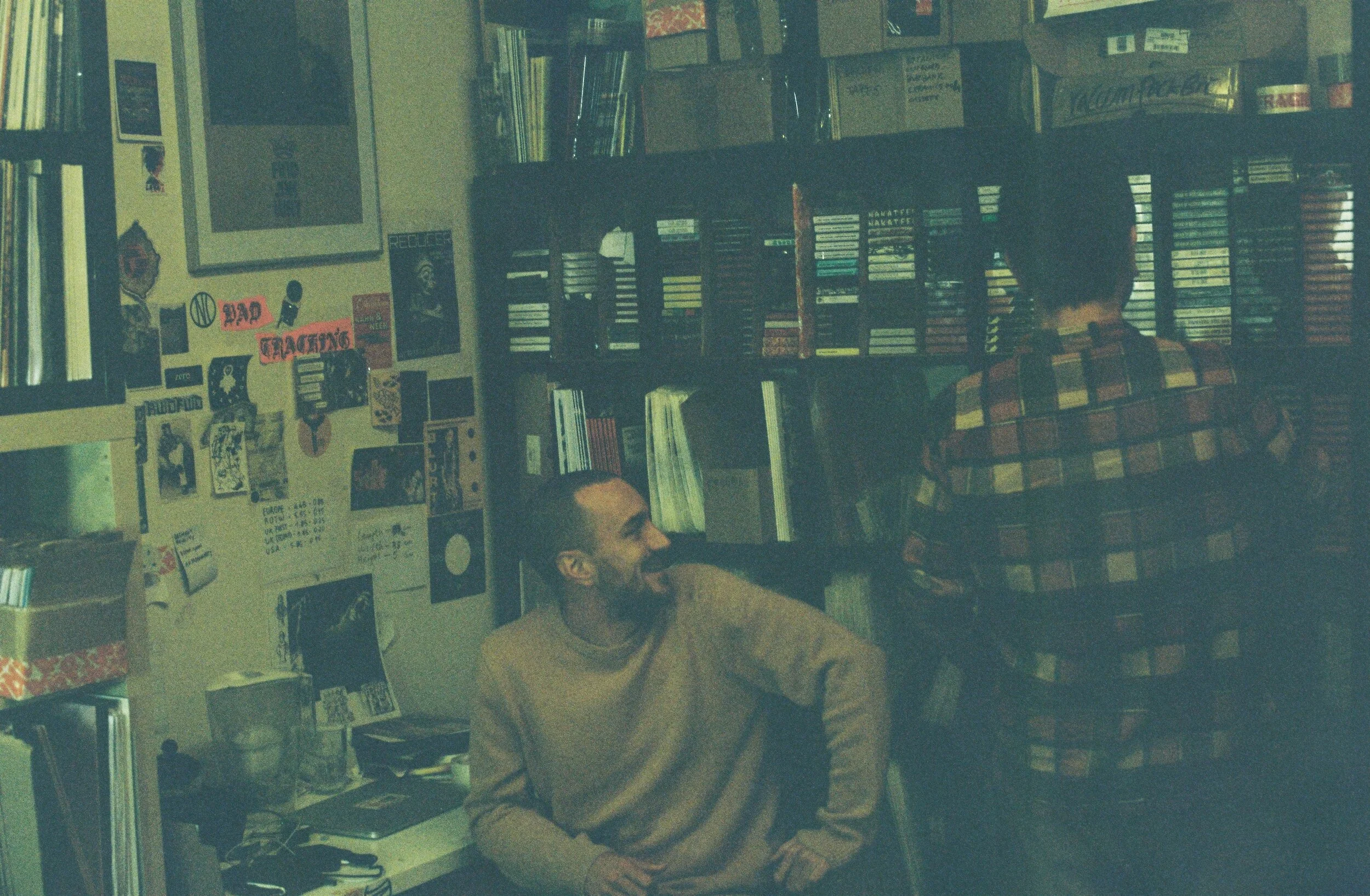

“I think we always tried our best not to get the labels and our own ventures too mixed up with the shop, especially in the early years,” says Davies as we talk in the RWDFWD HQ, affectionately known as ‘the beige cube’. “I was happy for it to just be its own thing, but then in more recent years I realised there is a benefit in linking the worlds a bit and letting people know what labels we run from the shop. It's a survival thing. It made a bit more sense to try and tie it all together.”

Survival is an inescapable topic when Davies, Digard and I discuss RWDFWD at length, given the shop’s emphasis on vinyl and physical media in general. The music industry and vinyl specifically have had plenty of make or break moments in the past, and we’re certainly in one now. Amongst the myriad issues facing vinyl, the spiraling lead times to get new music pressed up make it increasingly marginalised as a medium for DJs.

“If you're really desperate to put tunes out, you probably wouldn't do vinyl, you'd just whack it up on Bandcamp or Beatport or whatever,” says Digard. “That's not really what we're trying to do. It's more like, you could play anything that we've put out over the last 10 years and it still sounds good now, it's not disposable. I hope...

“Out of a lot of other scenes, the dubstep scene is still fairly vinyl focused, isn’t it? More than, say, drum & bass, for example, which is like non-existent. But I think what we've been stocking has shifted, hasn’t it?”

“Yeah. I’m not sure if that's anything to do with the vinyl though,” says Davies. “I think it's also our taste, isn't it? I was always into other music as well, and happy to stock records that weren't for the club on the shop. But there has been a shift with people buying more home listening records now. It seems harder to shift dance music records. Maybe that is partly to do with the way that the shop’s been curated over the years, but the word on the street these days is most shops and labels are focused on putting out LPs rather than a two-track single.”

“I think it’s a good thing, really,” says Digard. “You probably get more for your money. But then it's still fucking lovely seeing a nice single side. It’s sad that’s almost a luxury now.”

The other major conundrum facing shops like RWDFWD is the rise of Bandcamp, which has of course had a major impact on how artists generate a living, and how fans choose to support their favourite musicians. The sight of a major global platform acting in the interests of artists was heartening as live music revenues evaporated during the peak of the COVID lockdowns, but when fans and artists are doing business directly, shops like RWDFWD are quickly sidelined.

“It’s interesting with Bandcamp,” Davies muses. “We’re trying to figure out what the harmony of that is at the moment. It's been the saviour for artists getting the direct income from digital sales, but at the same time it feels a bit threatening to this network of record shops and the organic communities that grow around them. It feels a bit of a dangerous path to go down. It's not entirely evil, but I think there needs to be a bit more awareness for supporting community networks, rather than just individuals.”

Running a record shop is not something you take on unless you have a passion for it. The margins are slim, the stock is heavy and space-consuming, the market is shaky. But as was evident with the smile that broke across Digard’s face as he talked about the simple pleasure of a one-track side of wax, he and Davies are driven by an honest love of record culture. It’s old-world thinking maybe, but it’s a culture which has seduced repeated generations of music heads in the face of technological advances. Given his artistic life involves plenty of time in DJ booths, Davies is well placed to reflect on what vinyl represents at a time when it’s challenged on many fronts.

“You can do something interesting with CDJs that you can't do with records, but, from a more spiritual side of it, it's different. Even standing behind the decks in a club with these fucking bright CDJs blinding you, I find it really uncomfortable. We're spending so much time in front of screens these days, so when do you ever get away from it?

“I'm still perplexed every time I take a second to think about these black discs which rotate and somehow reproduce sound through vibration of a needle,” he adds. “I think that will always be something people will be interested in. I don't see any reason for it to go away. Whether it stays part of club culture in a general sense is another question, but I don't think they'll ever completely disappear.”

Even if things feel somewhat transitory in the present moment, RWDFWD emerged in what felt like a much simpler time for vinyl culture. In 2012 mainstream record consumption was yet to be fully re-ignited, but the barriers to entry seemed lower for anyone wanting to press up a record and put it out. Although CDJs had been an industry standard for some time, there was still an equation between vinyl and dubplate culture and dedication to the music, especially in dubstep and soundsystem circles. From a Bristol perspective, the likes of Pinch and Pev still cut their freshest tracks onto dub, and the hype around releases like Kahn & Neek’s Bandulu 12”s ensured hundreds of hyped-up heads were clamouring to cop a bit of ‘Percy’ when it hit the shops.

“I think we joined at a pretty good time,” Davies recalls. “It become a bit more of a viable underground option to do 300 records of something where maybe 10 years before people saw it as a big operation where you need a distribution deal and things like that.”

“For me the shop was more like a vehicle for presenting the label stuff how we wanted to,” says Digard. “Then other stuff on a similar tip got stocked as well. I don't think it was ever like, 'We need to be a massive online record shop.' It was a much more organic reflection of our tastes and interests in what was going on around us.”

Davies and Digard started the No Corner and Hotline labels the same year RWDFWD was set up, and the releases were key in marking out their musical community, not least the Young Echo collective. The first tape on No Corner was a Jabu / Killing Sound split, the A side of which came from an impromptu radio session recorded for the Tape Echo radio show on Sub FM in the same beige cube I’m sat in with Digard and Davies. Hotline launched with the seismic Backchat / Dubchat 12” from Kahn & Neek. When Kahn & Neek launched their Bandulu label with ‘Percy’, they slid out an upfront release to Davies and Digard. RWDFWD offered a platform for these and myriad other releases to reach the world without relying on external distribution.

Beyond the familial atmosphere of personal connections and collaborations, a key ingredient in binding together these various endeavours is Digard’s Tape Echo design work. Since he established his blog and started inking the labels in his vicinity, Digard has channeled a DIY ethic that calls right back to the roughshod days of punk zines and rave flyers. There’s no denying such aesthetics – lo-fi, grainy, scuffed around the edges – are a big draw when framed opposite the clean lines and crisp definition of the digital age, but there’s no contrivance in Digard’s dedication to his craft. Beyond the staunch independence and underground attitude such design implies, it’s also a simple case of what’s within reach and feasible for an operation with limited resources, just like it was in the nascent days of DIY.

“I always wanted to do record sleeves and make stuff look cool,” Digard explains. “I didn't know anything about web design. Tape Echo started off as a Tumblr, and I didn’t have a clue how to make it look nice, so I was like, ‘I'll just do it on paper, scan it in and put it up.’ All the more recent design work has just been a continuation of that, becoming interested in processes and exploring them.”

Amongst his scattered work for No Corner, Hotline, Dubkasm, Tectonic to bigger labels like Warp and On-U Sound, you can see Digard experimenting and working out techniques as much as he’s pressing on with a surefooted style. From the warts n’ all typewriter scans on the Tape Echo blog to the reams of photocopier textures, everything hangs together under the same veil of stubborn anti-slickness. Much like the communities and scenes the music emerges from, everything’s rooted in real life tools and creative workarounds.

The latest treasured weapon in the Tape Echo arsenal is a thermal printer, normally used for printing trade receipts and invoices, now re-purposed to make mixtape sleeves for RWDFWD and other series’.

“If you run images through it, it treats them in a really mad way,” Digard enthuses. “We spent about 400 quid on it two months into the pandemic when we couldn't get to the printers to do any photocopy stuff.”

“It’s a graduation from Abdul's photocopier,” Davies adds. “Abdul’s shop had a 5p-a-copy photocopier that Alex found out about, and he was just rinsing it, fucking around with the images as they're being photocopied.”

“It had a scratch on it,” Digard continues, “or there was a couple of dead pixels in there, and it put two lines down the middle of just about everything. There's an era of flyers, and I'm pretty sure [Ossia’s debut 12”] Red X has it on there as well, these re-scan bits with the two lines down it. We went in one day and it had gone. The goal is still to get a photocopier.”

Digard and Davies’ passion for these parts of the process of making records speaks for itself, and it manifests in so many ways. The tales keep spilling out about the lengths they’ve undertaken to present theirs and their friends’ work in imaginative ways with limited means, from buying offal from the butcher for an asda 12” to scaring the general public in a goat mask for a DJ Ape music video. Compared to the constellation of labels close to RWDFWD, the look of the website is a little more neutral – at one point Davies refers to it as a mothership of sorts holding everything together without displaying any sense of favouritism. And yet it still makes sense as an extension of this charmingly grimy creative pool.

“A big reason why we're here is this friend group that was around us were inspiring us with what they were doing,” says Davies. “Maybe we were inspiring them with how we were running things. It was a nice circle, and it still is, expanding in different directions, and everyone moves in their own ways as well.”

Beyond its immediate circle of labels though, there’s a broader community of music culture which folds into the fabric of RWDFWD’s identity. In its infancy as the Peng Sound! Big Cartel site, the operation was limited to 10 records, but with only a couple of releases to their name, Davies and Digard had capacity to carry someone else’s work. From running his Peng Sound! parties, Davies had fostered a few friendships in the music scene, including with Jackson Bailey (aka Tapes) and Dubkasm’s Stryda. What began as casually asking for a few spare records to stock soon gathered steam, not least when Dubkasm opted to give Davies and Digard an exclusive on their Victory! 12”, leading to a landslide of orders.

Further afield, West Coast USA dub label ZamZam Sounds is a vital fixture on the RWDFWD stock lists, but it’s the more niche offerings which speak the most about the position RWDFWD holds on an international level. I comment on a 7” from seminal UK post-punk outfit Blurt I spot lurking in the corner of the office, which it turns out was released by a Russian label called Post-Materialization Music. Davies pulls out their latest release – a matchbox containing some un-spooled tape and one match.

“They got in touch at some point and just said, ‘do you want to stock some tapes?’ and a few months later they arrived smelling of nicotine. This is one of the most beautiful releases I've come across.”

As well as arty, punk-indebted releases from the global underbelly of music, RWDFWD fulfils a valuable role stocking all kinds of other records, tapes and merch. From thoughtfully selected new dubstep, techno and experimental releases to a steady stream of foundational roots, dub, steppas and dancehall, a scroll through the virtual racks is always enlightening. It’s not the same offering you’d find with another store, and the comparatively smaller stock serves as a benefit to be able to zero in on a more particular vibe, however open that might be.

“There's no need to have another Juno, Boomkat or Honest Jon's,” says Digard. “By definition, this occupies a different space.”

“I'm sure there aren’t many who love every single thing we put up,” says Davies, “but I'd like to think there's a bit of something there for everyone. I don't think music should be a linear process, so it's nice to disband any formulaic generalisations of what you're into.

“I played a gig in Switzerland about four years ago and the warm up DJs were just playing all these records that were blatantly from RWDFWD,” he laughs. “That was my first time realising maybe there is a very fragmented but international scene based around what RWDFWD stocks, and people's tastes are being informed by that.”

You could tell a lot about the RWDFWD attitude to stock selecting by looking at their approach to genre categorisation. The distinction between ‘Dancefloor’ and ‘Dancehall’, ‘Dub’ or indeed ‘Dubwise’ is not necessarily apparent – the tag on a particular release can be as irreverent as it is illuminating. It’s an impractical but pointed stance for the site to take – one which might sadly get lost in a planned re-build – but it echoes Davies’ comment about music as a non-linear experience. In the increasingly organised and suspiciously sculpted paths we take through the internet and communication, these illogical disruptions celebrate chance and a more organic kind of discovery.

This in turn says a lot about RWDFWD’s position as an online store as opposed to a bricks and mortar entity. Even if it doesn’t have a public physical manifestation, it still functions as a community venture, and the day-long takeover of Noods radio is a perfect example of that community in action. From the quiet mic chat of the early hours to the lively shouts in the background as Davies signs off over Anina & Guest’s live-DJ jungle hybrids, people are drawn in by what RWDFWD represents. Even if you can’t pick up a release over the counter and chat over the shop system, all the releases, the personal tone of the product descriptions and the abundance of low-key, hand-wrought wares all conjure up a tangible sense of the real world. In that way there’s no division between the work Davies and Digard do with RWDFWD and what they create as artists and relentless record label machines.

“The whole music industry is so digitized,” says Davies, “and everything happens via digital means of communication and so on. But essentially, it's just people trying to manifest themselves in some way, cave painting style, leaving something behind. I think our approach represents the fascination of seeing something become real. That's part of what keeps us going. We wouldn't be here if we were just sat in front of our laptop tapping away, uploading things to Bandcamp and seeing how many plays we're getting. All that stuff doesn't really fascinate us in the same way.”

“From buying records when I was 18 and thinking, ‘That looks so sick, it would be amazing to do one of those,’ to finally getting to do one and now having done so many, the buzz is still exactly the same,” says Digard. “‘How can we make this the best thing it can be? Could we spend an extra 100 quid and add an extra sticker or stamp, or screenprint it?’ Just to make stuff you're really hyped to pull off the shelf and be like, ‘Yeah, this is sick, we made this and it's all self-funded. It's proper DIY. There's not been any grants, sadly, no P&D, none of that. Just, I guess, stubbornness.”

The landscape for records and the music business in general is always in flux, but operations like RWDFWD are driven by much more than financial ambition. For Davies and Digard, their service to the culture, these plastic discs and the sounds contained within, is paramount – the will to adapt and survive is a logical by-product.